Development Log: ADHD Experience

Introduction

In this development log, I will explain the research, design decisions, technical processes, and ethical considerations behind my project. I have created a 3D 360 VR (virtual reality) experience aimed at people who may not understand what it is like to live with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). This direction was decided during my previous assignment.

Originally, my intention was to create a fully interactive VR game. However, I later realised that the scope of this idea was too ambitious given the time constraints and my current technical abilities. Developing a VR game would have required advanced optimisation techniques such as retopology and texture baking to reduce polygon counts and ensure the experience could run effectively in VR. Instead, I chose to create a guided 360 VR experience where the user can still look around and engage with the environment, but without interactive gameplay elements.

The aim of this experience is to communicate what it can feel like to be mentally overwhelmed through exaggerated visuals, lighting, and layered sound design. In the original game concept, the user would have needed to find medication to escape the chaotic room, which metaphorically represented the way ADHD can feel overwhelming and mentally exhausting. While this idea could not be fully realised, I adapted it into a narrative VR video that still conveys these themes.

I focused heavily on lighting, sound, and the blending of realism with abstract elements rather than pursuing hyper-realism, which would have significantly increased production time. This project has also given me ideas for future development beyond university, potentially expanding into an interactive VR experience that could be used in educational or seminar settings to help psychologists better understand patient experiences. As stated at the beginning of the video, this project reflects aspects of my own experience, having been diagnosed with ADHD in my twenties, and aims to encourage understanding and empathy towards people with neurological disorders.

Research

I have researched ADHD prior to attending university as part of trying to understand my own neurological condition and explore ways to manage it. One of the most relevant and recent studies I examined was by Zhu and Zou (2024), who discuss how people with ADHD commonly experience difficulties in regulating sensory input. Their research highlights how everyday environments can unexpectedly become overwhelming for individuals with this condition. This study provided a key foundation for my visual concept.

After reconsidering the original game idea, I realised that the experience did not need to be a complex interactive system in order to communicate its message. Instead, animation alone could provide a strong sense of what living with ADHD can feel like. This also reinforces the idea that the viewer is not fully in control of the situation. From personal experience, I often find myself acting without realising it, such as not listening during conversations. This is not due to boredom, but because a word or visual trigger can lead to a chain of thoughts that quickly spirals. As a result, attention shifts entirely, often without awareness, which can negatively impact personal relationships.

Another key area of research that influenced this project was executive dysfunction, discussed by Barkley (2015). He describes concepts such as “time blindness” and difficulties organising tasks across time. This directly informed my decision to use visual metaphors for clutter. The clutter in the environment is not intended to represent mess alone, but the feeling that every object is demanding attention at the same time.

From a technological perspective, I chose to produce a short immersive film rather than a game. Research by Radianti et al. (2020) and Makransky and Petersen (2019) was particularly important, as both argue that immersive media enhances a sense of presence, the feeling of truly being in a space. Makransky’s work suggests that immersive formats are especially effective for communicating abstract or complex experiences that are difficult to articulate verbally. As shapes and sounds predate language, a 360 VR video allows internal struggles such as ADHD to be communicated experientially. This medium challenges surface-level assumptions of laziness or dysfunction and instead allows viewers to feel what living with ADHD can be like for much of the time.

Concept Development

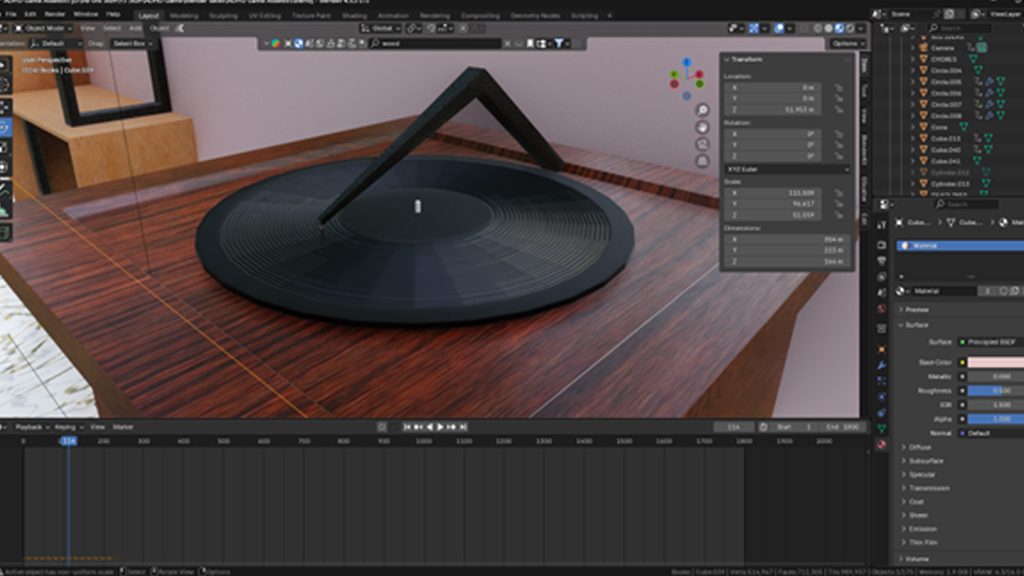

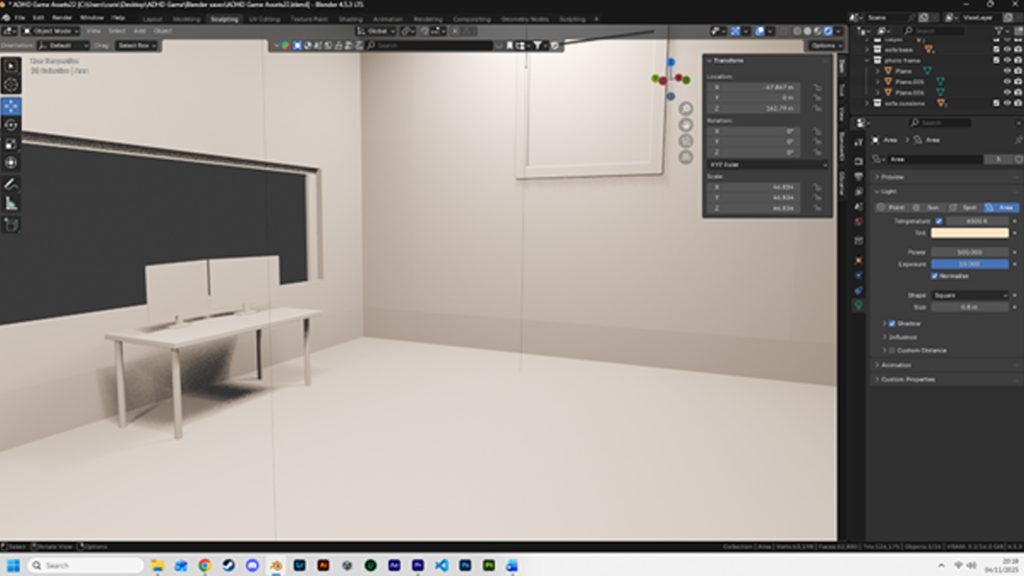

The narrative structure of this project is built entirely around contrast. It represents what many people with ADHD want: a simple, quiet life where they are organised, motivated, and not seen as a burden to others. This desire for calm and control informed the design of the first environment, which was intentionally created to resemble a normal, comfortable living space. The room includes familiar and personal items such as a couch with a blanket, a television on its stand, a computer desk for work, and a large framed image symbolising personal achievement. A vinyl player and speaker were added to reinforce the idea of calm through music. Soft lighting, neutral colours, and a large window allowing natural light were used to enhance this atmosphere. This environment functions as a control variable, allowing the viewer to establish a sense of stability, comfort, and normality. It represents the mental state I aim to be in, where tasks feel manageable and life feels structured.

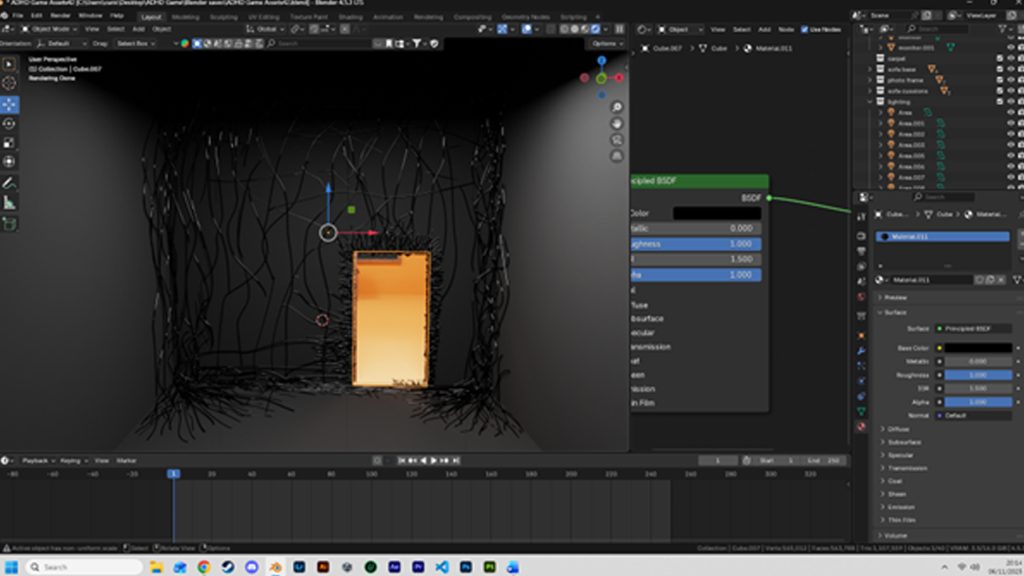

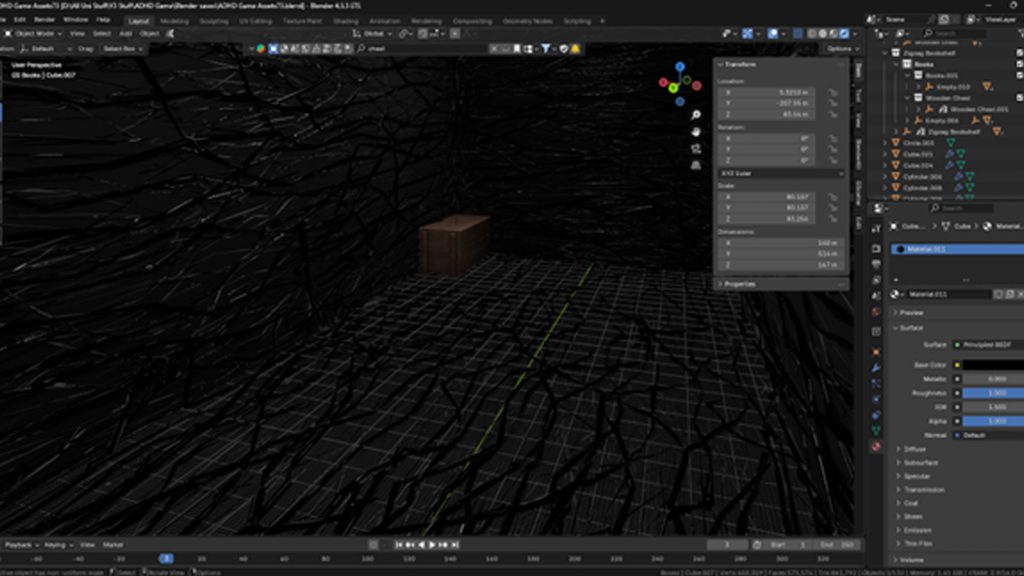

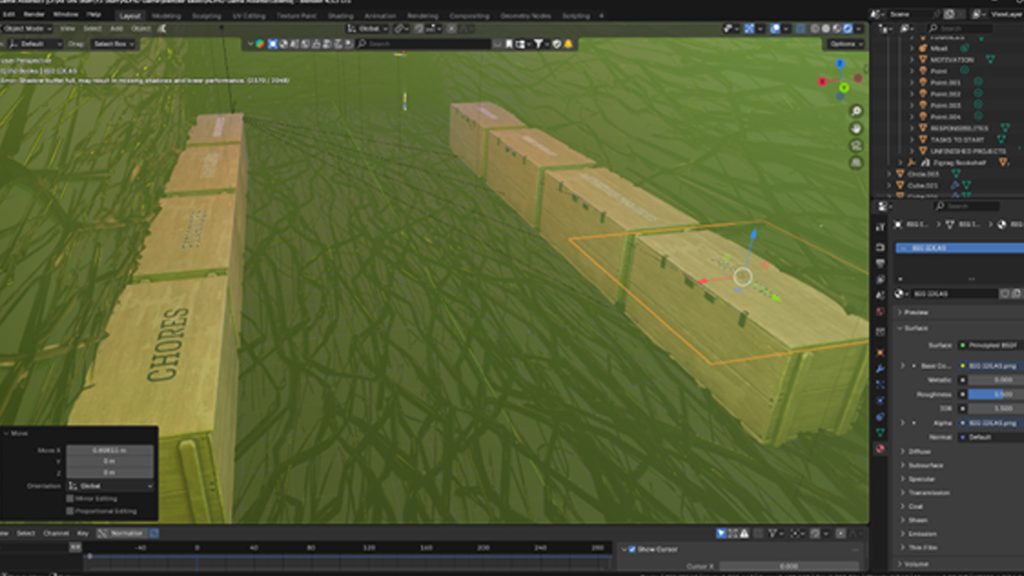

As the viewer moves through the space, they are pulled into the second environment: the “chaos room.” This room represents cognitive overload. Darker lighting and creeping vines were introduced to subtly shift the mood without making the space feel like a horror setting. The goal was not fear, but to cause discomfort, to reflect how mentally overwhelming ADHD can feel. To achieve this, I used visual metaphors informed by Barkley’s (2015) research on task paralysis and executive dysfunction. Multiple chests are placed around the room, creating a sense of being surrounded by responsibilities. These chests are labelled with terms such as “Motivation,” “Responsibilities,” and “Projects,” representing unfinished tasks, mental clutter, and competing priorities occurring simultaneously. This reflects the experience of having multiple “mental tabs” open at once, all demanding attention.

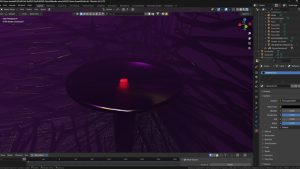

A key element within this space is the medication placed at the back of the room. It is intentionally unnamed and ambiguous, reflecting the uncertainty many people with ADHD face when seeking treatment. Medication is not guaranteed to work for everyone, and for some, including myself, alternative coping strategies are required. The medication is coloured red to convey uncertainty and intensity. It could help, but it could also cause concern.

Throughout this scene, the viewer is exposed to flashing lights, overlapping thoughts, and layered sound, reinforcing sensory overload. The narrative concludes with the viewer consuming the medication and returning to the calm room. This ending reinforces the idea that while treatment can help manage ADHD, it is not a permanent cure, but part of an ongoing cycle.

Blender and Technical Workflow

Blender was used for all 3D modelling, texturing, animation, lighting, and rendering within this project. Adobe Illustrator was used to create the text labels for the chests, as adding text geometry directly in Blender would have significantly increased the polygon count. At this stage, the scene was already approaching one million polygons, so this decision was made to optimise performance.

Visual content displayed on the television was taken from a previous project I created last year and applied to a simple plane rather than a 3D screen model, again to reduce resource usage. All audio elements, including voice recordings and music, were assembled and synchronised in Adobe Premiere Pro.

All objects within the scene were modelled from scratch, which explains the initially high polygon count. At its peak, the scene exceeded 4.5 million polygons. To resolve this, extensive use of the Decimate modifier was required, reducing the final scene to approximately 970,000 polygons. This optimisation significantly improved viewport performance and rendering times.

Camera settings were configured using an Equirectangular projection, following techniques introduced during the previous assignment. The render resolution was set to 4096 × 2048, producing a standard 2:1 aspect ratio required for 360-degree video. This higher resolution was chosen because 1080p footage often degrades noticeably when uploaded to YouTube, particularly for VR content. The increased detail ensures that when viewers pause and look around the scene, the environment remains visually consistent and immersive.

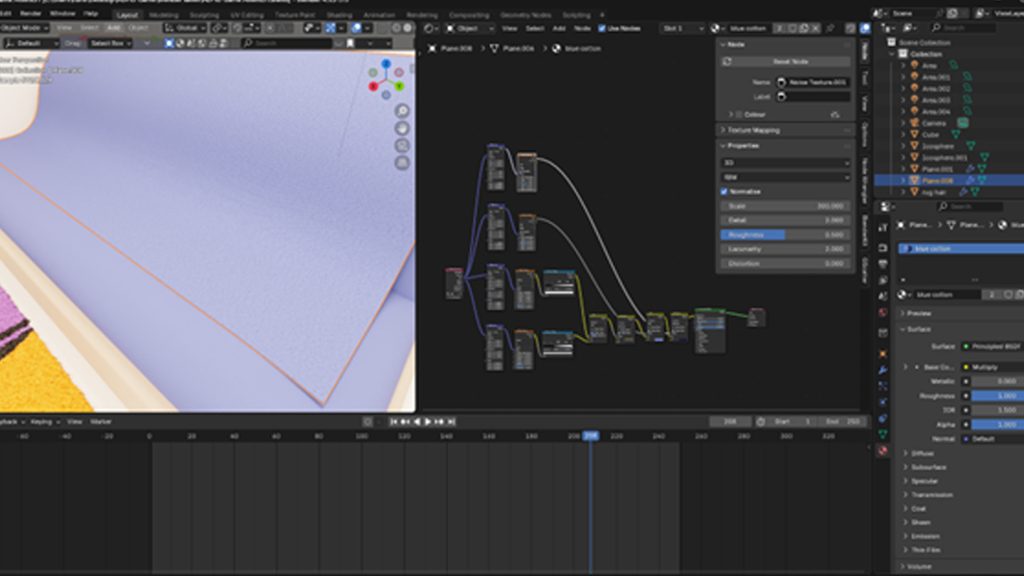

All textures were created procedurally using shader nodes and geometry nodes. Wooden objects shared a base texture but were individually adjusted to avoid repetition and to create variation between assets. Cloth simulation was used for elements such as the blanket on the couch, utilising both active and passive physics, followed by light sculpting to achieve a natural resting position.

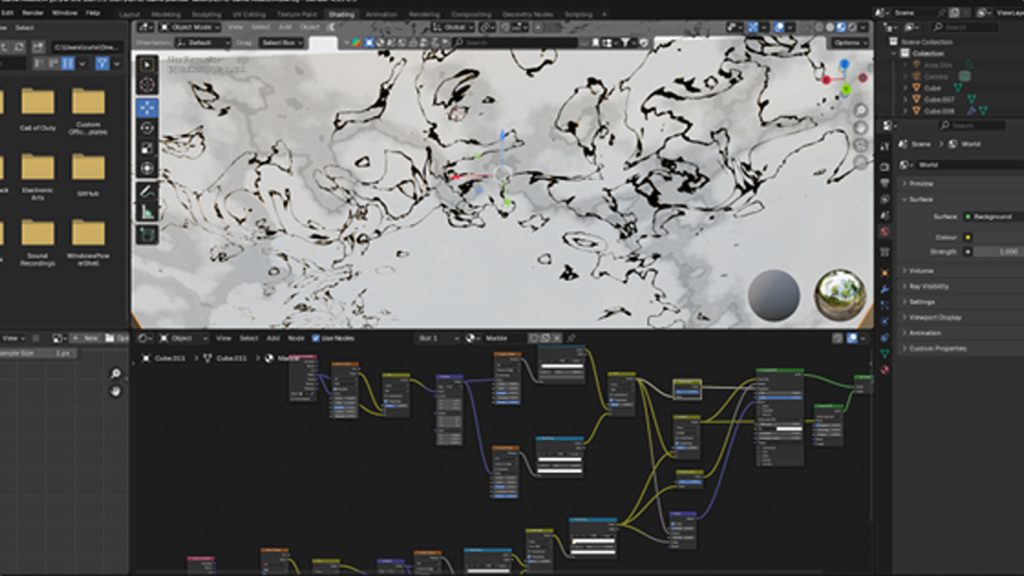

The vines in the chaos room were created using Bezier curves, with modified geometry settings to achieve circular growth patterns and colour variation. Each vine was manually drawn and constrained to nearby surfaces to ensure they wrapped naturally around the environment. Due to their complexity, individual vine meshes reached up to 900,000 triangles, making decimation essential to maintain performance. The only object not decimated was the Bauhaus-style rug in the calm room, as reducing its geometry noticeably impacted its visual quality.

Originally, the camera movement was intended to simulate walking using head-bob motion. However, this was later removed as viewer movement was not essential to communicating the project’s narrative. Instead, a smoother camera path was used to maintain focus on the environment and reduce unnecessary complexity.

Blender’s Cycles rendering engine was selected to achieve realistic global illumination, as Eevee currently struggles with lighting accuracy in 360-degree VR environments. Initial render times averaged between 45 seconds and one minute per frame. By adjusting lighting, sampling, and noise settings, this was reduced to approximately 18 seconds per frame, resulting in a total render time of around six and a half hours. The OptiX denoiser was used in the viewport for performance, while OpenImageDenoise was used for the final render.

To further reduce render time, the animation was exported directly as a video file rather than as individual PNG frames. This reduced the total number of frames rendered from 3,680 to 1,840, significantly decreasing overall render duration. The final render was then imported into Adobe Premiere Pro, where voice recordings, warning screens, and the two music tracks were added. The completed video was exported using YouTube’s recommended settings and processed with a metadata injector to enable full 360-degree VR playback.

Final Thoughts and Video

To reiterate a point made earlier, this project is something I would like to develop further in the future. Ideally, I would reintroduce interactivity and rebuild the experience using Unreal Engine 5, allowing for higher-fidelity graphics and real-time interaction. This would enable the inclusion of features such as hand tracking, allowing users to physically interact with the environment. In doing so, the chaos room could be expanded into a more complex navigational space, reinforcing the struggle of attempting to regain control while overwhelmed by sensory and cognitive overload.

However, within the scope of this module, the project successfully achieved its intended aims. The final outcome demonstrates a technically competent execution, a research-informed design process, and a commitment to ethical storytelling when representing a neurodivergent experience. While the work does not attempt to represent every individual with ADHD, it offers an honest and respectful insight into one aspect of the condition, using immersive media to communicate experiences that are often difficult to articulate through traditional formats.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1mijhXXcPkf7SROC7mZp1hA8FY1SXZ1-Q/view?usp=drive_link

References:

Barkley, R.A. (2015) Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th edn. New York: Guilford Press.

Lau, H.M., Smit, J.H., Fleming, T.M. and Riper, H. (2023) ‘Serious games and virtual reality interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, pp. 1–17.

Makransky, G. and Petersen, G.B. (2019) ‘Immersive virtual reality and learning: A meta-analysis’, Educational Psychology Review, 31(2), pp. 1–27.

Radianti, J., Majchrzak, T.A., Fromm, J. and Wohlgenannt, I. (2020) ‘A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education’, Education and Information Technologies, 25(1), pp. 1–38.

Wollberg, S. (2018) Inclusive Design for Neurodiversity. Available at: https://sarawollberg.com

(Accessed: 18 December 2025).

Zhu, Y. and Zou, L. (2024) ‘Sensory processing differences in adults with ADHD’, Brain Sciences, 14(6), pp. 1–15.

prodbyIOF (n.d.) Audio track. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7hpfifR6JaM

(Accessed: 2 January 2026).

NoCopyrightSounds (n.d.) Audio track. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0IpIPb_5ktw (Accessed: 3 January 2026).