Ethical and Sustainable Farming – Ruminants and Regenerative Agriculture

The current state of farming presents a serious sustainability issue, not only concerning human health but also in terms of animal welfare and environmental integrity. Industrial agriculture—especially factory farming and large-scale monoculture vegetable production—has been shown to contribute to the decline of soil quality, biodiversity, and ethical animal treatment (Gliessman, 2015). While the shift towards plant-based diets is rooted in an ethical desire to reduce animal suffering and environmental harm, it is not without its unintended consequences.

Monoculture vegetable farms, often required to meet the increasing demand for plant-based foods, rely heavily on artificial fertilisers and pesticides. These substances strip soil of its nutrients, pollute waterways, and reduce long-term land productivity (FAO, 2017). Such practices result in the loss of pollinators, reduced biodiversity, and diminished carbon sequestration. According to Montgomery (2007), soil degradation now affects one-third of the planet’s arable land, in part due to unsustainable farming practices.

In contrast, reintroducing ruminant farming through regenerative agriculture offers a more holistic and sustainable model. Ruminant animals—such as cows and sheep—play a vital ecological role when integrated into natural systems. Their manure helps to regenerate the soil, increasing its organic matter and supporting microbial life. Grasslands maintained by grazing animals have been shown to store more carbon than forests in some cases (Teague et al., 2016), offering a net-positive solution for the environment when managed properly.

By rotating grazing areas and mimicking natural herding patterns, regenerative farmers can improve soil structure and encourage plant biodiversity. This practice, known as rotational grazing, enhances carbon sequestration and supports resilient ecosystems (Savory Institute, 2020). Furthermore, regenerative ruminant systems reduce the need for synthetic fertilisers, lowering emissions while restoring land health.

Importantly, this form of agriculture also enhances animal welfare. Unlike industrial systems, regenerative farms offer animals open space, natural diets, and minimal stress. Studies show that animals raised in such environments exhibit lower cortisol levels, suggesting better welfare outcomes (Fraser et al., 2013). Healthier animals produce higher quality meat and dairy products, aligning ethical considerations with nutritional benefits.

This animation project seeks to raise awareness about regenerative ruminant farming as a sustainable model that supports animals, people, and the planet. The target audience includes environmentally conscious consumers, educators, and students. The aim is to challenge assumptions that plant-only agriculture is always the most sustainable and to instead highlight practices that work in harmony with nature. Through visual storytelling, the animation will portray a transition from barren, overworked land to flourishing green pastures—made possible by the natural cycling enabled by ruminants. By showcasing this transformation, the project encourages a more nuanced understanding of sustainability in farming.

Conceptual Design and Transition Planning

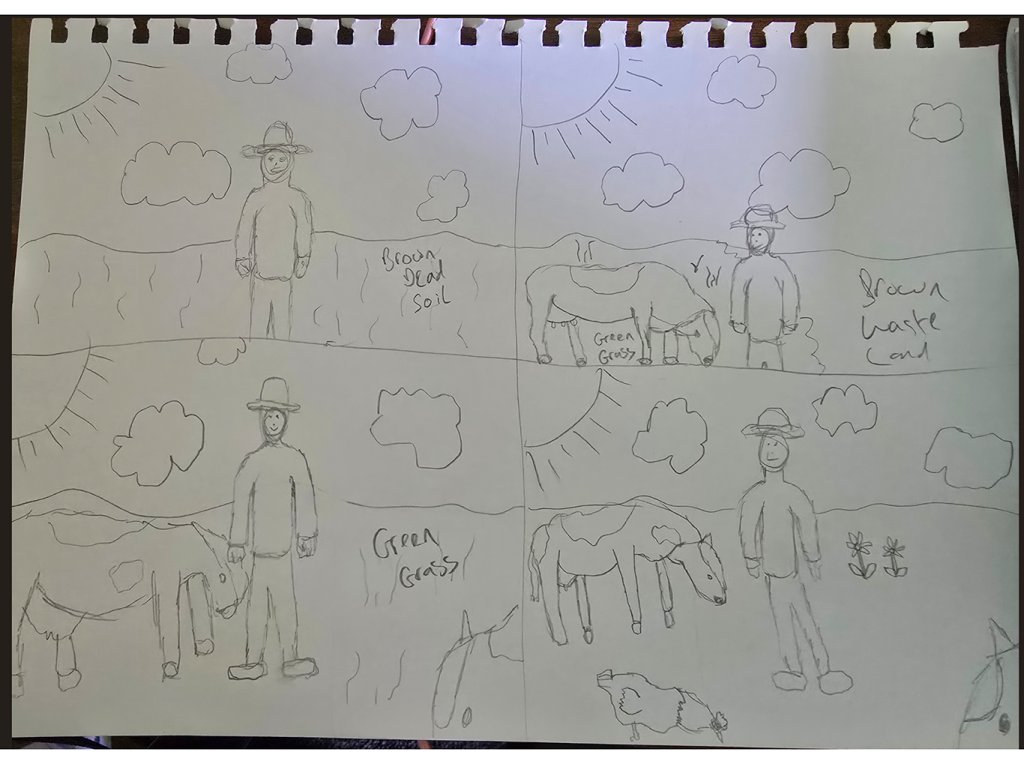

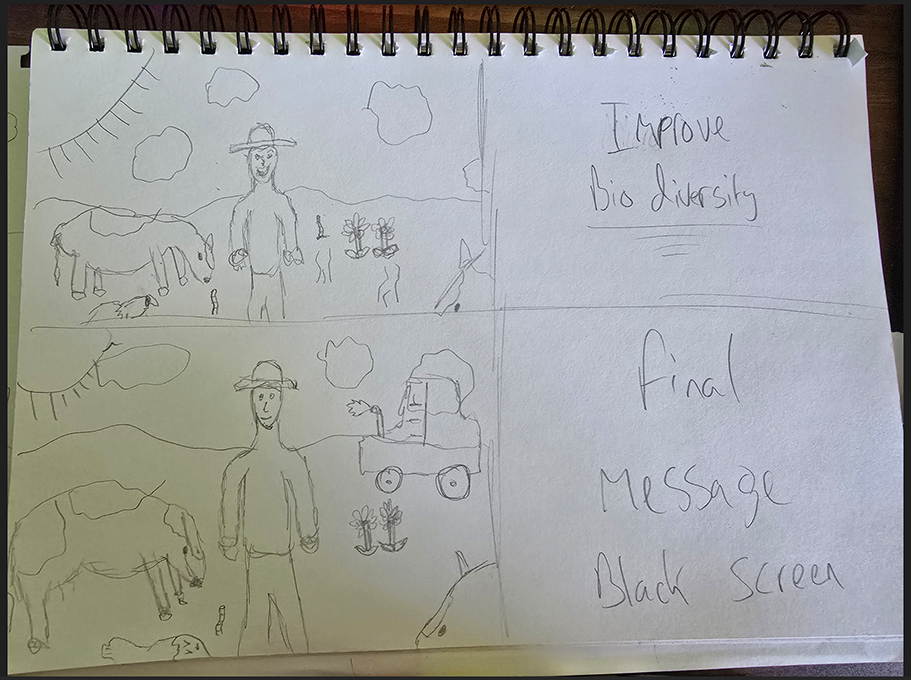

Planning this animation presented a number of challenges, particularly due to my limited drawing skills and my tendency to set high expectations for creative output. These constraints, however, encouraged me to approach the project in a more inventive and adaptive way. The conceptualisation phase took longer than anticipated, as I explored several different formats for delivering my message in a visually engaging and meaningful way.

Initially, I envisioned creating a stop-frame animation using printed drawings of the main characters, such as a farmer and a cow. My idea was to illustrate each frame by hand, print the individual assets, cut them out, and animate them through sequential photography. However, once I began the production process, I found myself without access to a printer. This limitation forced me to rethink my approach.

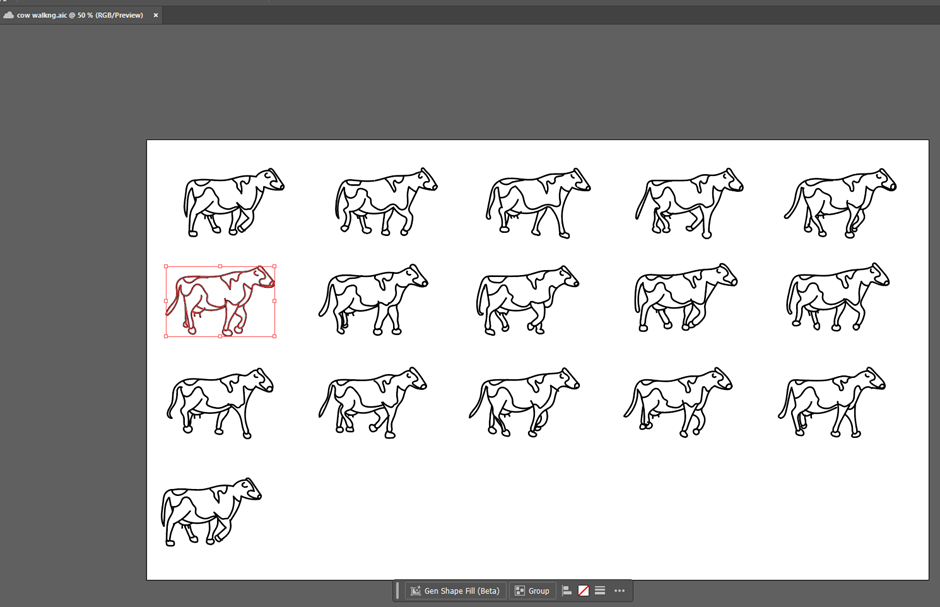

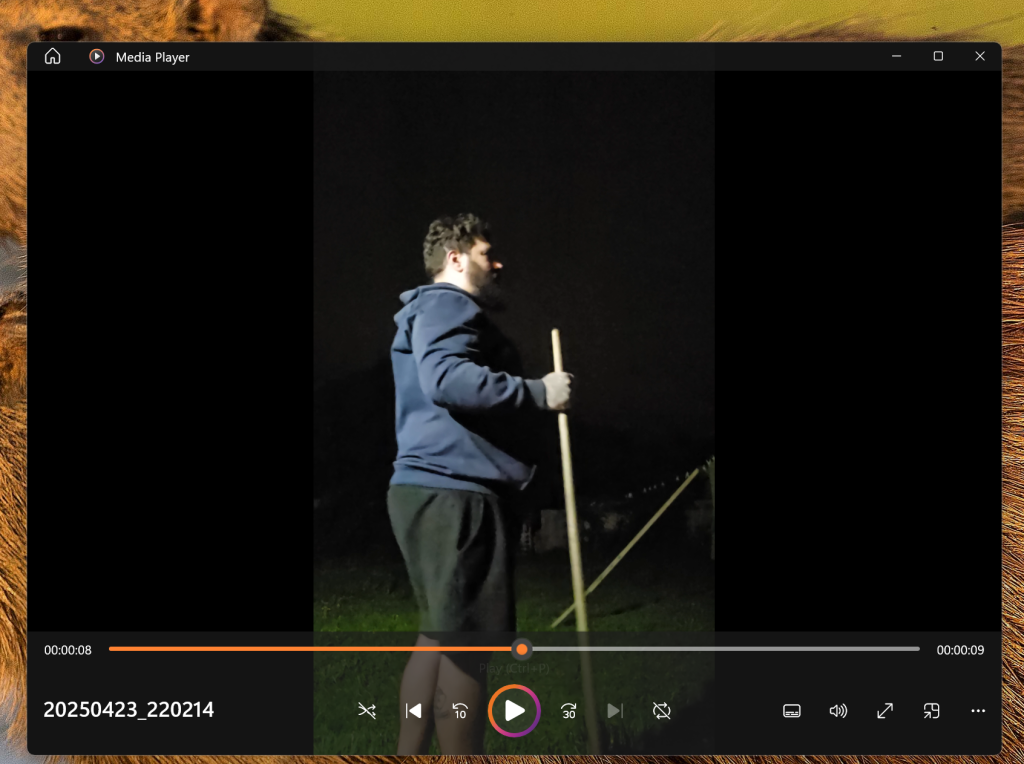

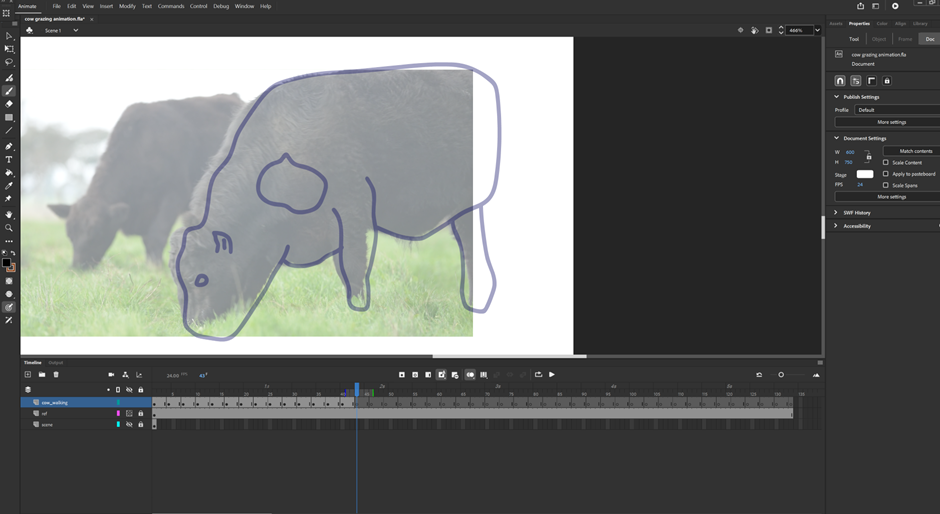

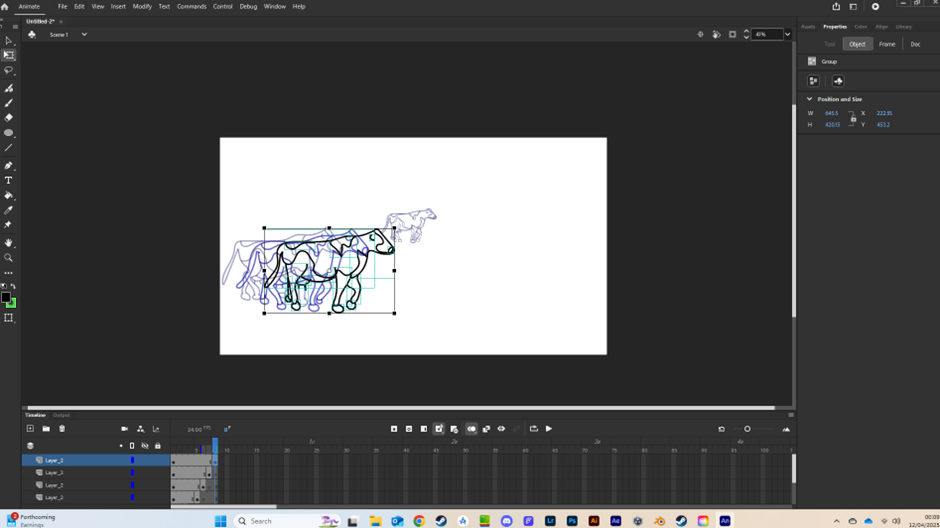

To save time and maintain a sense of movement, I attempted to use rotoscoping—filming myself walking and then tracing over the footage to create a believable walking cycle. I asked my partner to record reference footage for this purpose. After several attempts at rotoscoping, I realised that the technique required more technical precision than I could confidently achieve in the available timeframe. As a result, I pivoted once more, opting to simplify the animation style into a hand-drawn cartoon approach with limited movement.

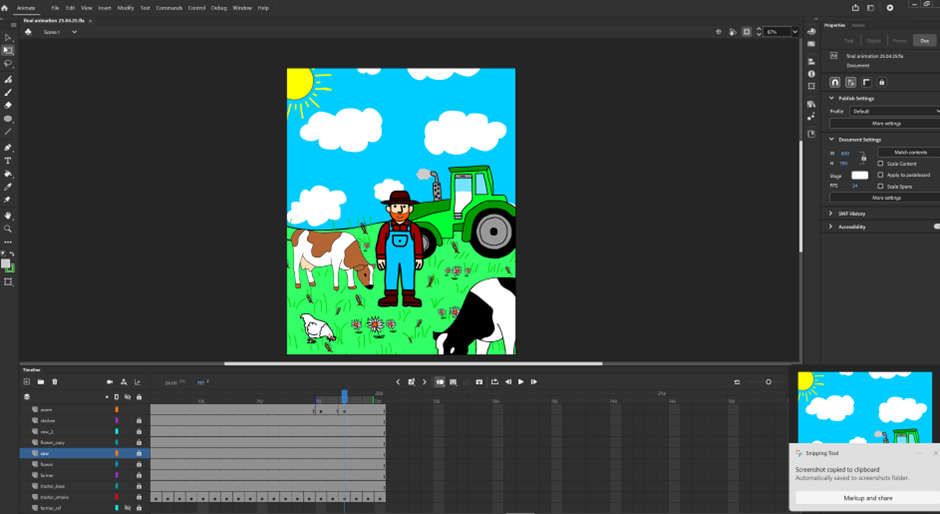

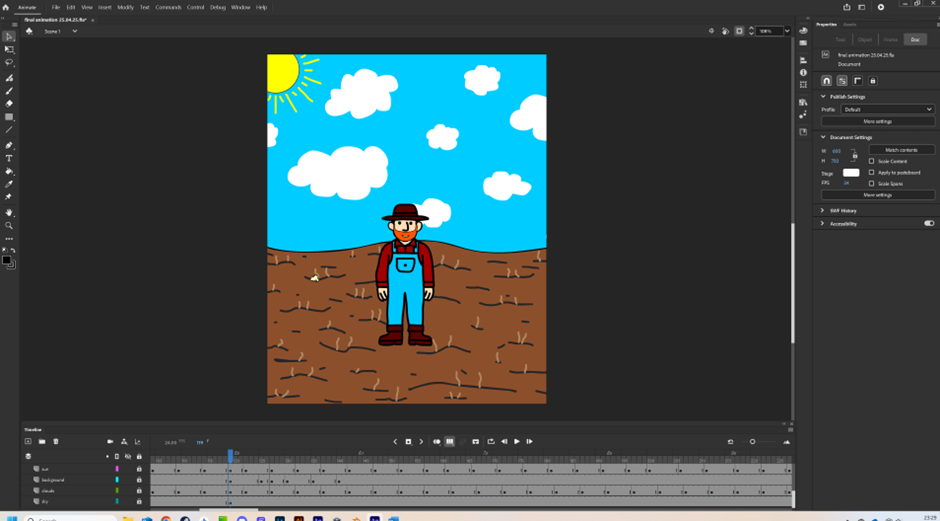

The final storyboard reflects these choices and constraints. The animation features elements that “pop” into the frame with minor movements, adding a sense of liveliness while keeping the process manageable. The sequence begins with the farmer (representing humanity) entering a barren, lifeless field. The farmer introduces livestock—cows and other ruminant animals—as symbols of regenerative farming. With their arrival, the soil visually transforms, changing from dry and exhausted to vibrant and fertile. Flowers bloom, insects return, and colour floods the screen, reinforcing the theme of environmental restoration.

To help drive the message visually, I deliberately used a shift in colour palette—from dull browns and greys to lush greens and bright tones. This transition represents not just the rejuvenation of the land but also the revitalisation of ethical and sustainable farming practices. Simple text overlays appear at key stages of the animation to reinforce the main points, keeping the messaging clear and accessible to a general audience. In planning this animation, I drew inspiration from visual communication strategies recommended by Edward Tufte, including layering, small multiples, and data-ink ratio (Tufte, 2001). These helped guide my decisions on visual economy and clarity. The storyboard process taught me that effective communication doesn’t always require complex techniques—sometimes, the simplest visuals paired with thoughtful transitions can deliver the strongest message.

Visual Design Treatment – Applying Edward Tufte’s Theories

In developing the visual approach to my classical animation project, I drew significantly from the theories of Edward Tufte, whose principles of information design offer valuable insights into presenting complex messages with clarity, precision and integrity. Though originally designed for data visualisation, Tufte’s five key theories—data-ink ratio, small multiples, layering and separation, integration of evidence, and avoidance of chartjunk—can be effectively adapted to visual storytelling and animation, especially when the message centres on sustainability and ethical topics.

My animation, which communicates the environmental and ethical benefits of regenerative ruminant farming, uses visual clarity and minimalism to deliver its message without overwhelming the viewer. I interpreted Tufte’s data-ink ratio principle by ensuring that every drawn element in my animation served a clear communicative purpose. There are no unnecessary embellishments or distracting visuals—each frame is carefully designed to deliver core ideas in the most direct way possible. For example, when the barren soil transforms into rich, biodiverse land, the visual change is purposeful, emphasising cause and effect without clutter.

The idea of small multiples is reflected in how I repeat simple imagery to reinforce key ideas. Flowers, insects, and changes in soil are shown incrementally, each reinforcing the broader message of environmental restoration. These small visual cues act as repeating units that the viewer can easily interpret across different frames. This not only enhances comprehension but also supports memory retention—viewers clearly understand that each returning element represents a shift toward sustainability.

Layering and separation were used effectively to guide attention and simplify complex scenes. For instance, when text overlays appear, they are presented on neutral, uncluttered areas of the screen to ensure readability and avoid visual confusion. I used colour contrast to separate background and foreground elements, helping the viewer distinguish between action and setting. The transition from lifeless brown landscapes to vibrant greens not only conveys ecological change but also separates “before” and “after” states in a clean, narrative-friendly way.

Tufte’s principle of integration of evidence was especially useful when combining text and image. Rather than separating narration and visuals, I synchronised them: when animals are introduced into the scene, text appears stating the associated benefit (e.g., “Improves soil fertility” or “Supports biodiversity”). This pairing of visual and verbal content creates a stronger link between evidence and conclusion, ensuring the audience understands not just what is happening but why it matters.

Finally, I carefully avoided what Tufte calls chartjunk—visual elements that serve no real purpose or distract from the core message (Tufte, 2001). Rather than fill the animation with irrelevant effects or overcomplicated transitions, I adopted a hand-drawn, minimalist style that prioritises message over spectacle. This decision also reflects the “earthy” subject matter: the simplicity of the visuals mirrors the simplicity and natural rhythm of regenerative farming itself.

In conclusion, Edward Tufte’s theories provided a clear framework for creating an informative and engaging animation. By applying these principles, I was able to deliver a message about ethical and sustainable farming in a way that is visually coherent, emotionally engaging, and intellectually accessible.

Relevant Animation History – Ethical and Sustainable Themes in Animation

Animation has long been used as a powerful medium to explore complex ethical and environmental themes. In developing my own animation on regenerative farming and biodiversity, I looked at several examples that successfully communicate sustainability issues through creative visual storytelling. The following three animations provided valuable inspiration in terms of technique, tone, and message clarity.

1. “Save the Soil” by Conscious Planet

This animated short, created by the Conscious Planet movement, focuses on soil degradation and the importance of sustainable land use. It uses a bright, friendly art style and simplifies the issue so that it’s accessible to all age groups. The animation combines narrated facts with a visual journey of land going from fertile to barren due to modern agricultural practices, then returning to health through soil conservation. This directly influenced my own visual narrative, particularly the transition from lifeless, brown soil to lush, colourful landscapes. It validated the importance of a visual metaphor to represent ecological recovery, which I also used to mark the impact of reintroducing animals to land.

2. “There’s a Rang-Tan in My Bedroom” by Greenpeace

This emotive animation by Greenpeace exposes the environmental destruction caused by palm oil production, using a child’s perspective and hand-drawn illustration. Its emotional appeal, combined with a clear call to action, left a strong impression on how animation can humanise environmental issues. The style inspired the more personal tone of my project; although my animation isn’t told through a child’s voice, I designed the farmer as a relatable everyman figure who represents the viewer. The use of character-driven storytelling in this example shaped my decision to centre the animation around a farmer guiding the land’s transformation.

3. “The Story of Stuff” by Annie Leonard

This classic animation explains the lifecycle of material goods and critiques consumer culture. Though primarily a motion graphic, it uses simple visuals and voiceover to deliver complex socio-economic ideas. I was inspired by how it maintains clarity without overcomplicating visuals, and how it aligns visuals tightly with spoken text. In my animation, I adopted a similar approach by timing my on-screen text and scene transitions with the narration to ensure that each visual has a direct, purposeful relationship with the message being delivered.

Each of these animations shows how sustainability issues can be communicated clearly and powerfully through visual metaphor, relatable characters, and a restrained aesthetic. They avoid over-stimulation, focusing instead on clarity and emotional engagement—principles I incorporated by limiting my colour palette, using clear contrasts to indicate change, and keeping animation movements minimal yet meaningful. Ultimately, these historical examples confirmed that animation doesn’t need to be complex to be effective. Simplicity, storytelling, and emotionally resonant imagery have far greater impact when addressing ethical topics. These influences helped me maintain focus on my core message: regenerative farming is not just better for animals but also vital for the planet’s ecological health.

Classic Animation – ‘Regenerative Farming’

References

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) (2017) The future of food and agriculture – Trends and challenges. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Fraser, D., Weary, D.M., Pajor, E.A. and Milligan, B.N. (2013) ‘A scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns’, Animal Welfare, 7(3), pp. 187–205.

Gliessman, S.R. (2015) Agroecology: The ecology of sustainable food systems. 3rd edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Montgomery, D.R. (2007) Dirt: The erosion of civilizations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Savory Institute (2020) What is Holistic Management? Available at: https://savory.global/ (Accessed: 12 April 2025).

Teague, R., Apfelbaum, S., Lal, R., Kreuter, U., Rowntree, J., Davies, C., Conser, R., Rasmussen, M., Hatfield, J., Wang, T. and Byck, P. (2016) ‘The role of ruminants in reducing agriculture’s carbon footprint in North America’, Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 71(2), pp. 156–164.

Tufte, E.R. (2001) The visual display of quantitative information. 2nd edn. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Greenpeace (2018) There’s a Rang-Tan in My Bedroom [Online video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Ha6xUVqezQ (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

Conscious Planet (2022) Save the Soil Animation [Online video]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=txj_3C8aA0o (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

Leonard, A. (2007) The Story of Stuff [Online video]. The Story of Stuff Project. Available at: https://www.storyofstuff.org/movies/story-of-stuff/ (Accessed: 24 April 2025).